Having an understanding of locomotion can help to:

- Evaluate the conformation and gait of any dog.

- It can be used diagnostically to determine causes and location of lameness.

- Post-treatment it can be used to assess rehabilitation from injuries.

- In the competitive dog it can be used to assess any subclinical factors that might affect performance.

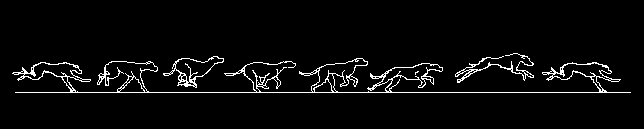

Dog Running, Sequence of Gait

Structure Basics of Locomotion

Canine locomotion can be compared to a symphony orchestra playing a composition. “All parts must blend into a harmonious pattern, from the gentle sway of the head and tail for balance to the coordinated efforts of each limb and body muscle to accomplish its special function. Conversely, also like an orchestra, if all movements are not attuned to the whole, a major fault should be evident” (Roy 1971) .

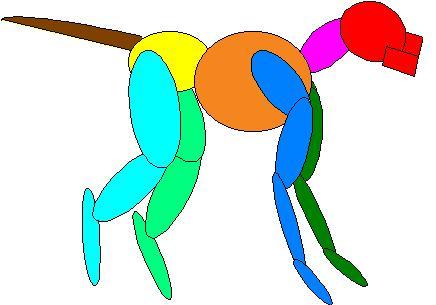

The canine structure is divided into segments when analyzing motion. The axial vertebral column is made up of many joints and is divided into anatomical segments. The cranial segment is the head, followed caudally by the neck (cervical), thoracic, abdominal (lumbo-sacral), and tail. The appendicular segments are the front legs and the back legs. These are subdivided into smaller segments by the leg joints: shoulder, elbow, carpus, hip, stifle, tarsus & phalanges. Locomotion as a whole is a result of the individual movements of these segments. Gait analysis is used to assess the movement of each of the individual joints and how they affect locomotion.

Symmetry of the Dog’s Body

Axial Skeleton includes:

- Head

- Neck

- Thorax

- Abdomen

- Pelvis

- Tail

|

|

Quantitative gait analysis assigns numerical values to motion and includes the application of kinetics and kinematics. The force plate is an example of kinetic analysis being used to assess lameness. The numerical values of the ground reaction forces are used to determine variances of gait. Video analysis is used to assess the kinematic parameters of locomotion. With kinematic analysis, linear parameters of movement can be measured to assess horizontal and vertical motion. Also, angular parameters can measure the degrees of movement of the joints to analyze specific joint motion.

Gait Analysis

Canine locomotion can be used to assess the function of the body as a whole by evaluating the functions of it’s individual components. The anatomy of the dog’s body is designed symmetrically. The right side should mirror the left side. In theory, then, the movements of the right side should mirror the movements of the left side. This is true to an extent, with variances due to laterality, in other words some dogs are right-handed and some dogs are left-handed.

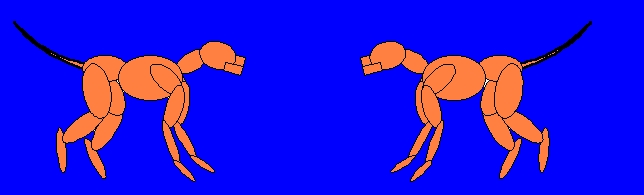

Computerized Analyzed Dog Gait

Digitized Video of the Walk gait in the dog.

Locomotion

To evaluate balanced body movement we can analyze canine locomotion. The common name for analysis of canine locomotion is “gait analysis”. There are various forms of gait, which are a combined result of body anatomy and velocity of movement. Gaits can be defined as symmetrical or asymmetrical. While in a symmetrical gait, the movements of the sides of the dog mirror each other. Examples of these gaits are the walk, trot, and pace. In an asymmetrical gait the movements of the two sides are not the same. The running gallop is an example of this type of gait.

Trot

The best gaits to use for gait analysis are the symmetrical gaits, the walk or the trot. It is easier to pick up abnormal movement while a dog is moving symmetrically. The trot is a two phase gait, and the gait that is utilized by our CAV motion analysis system we currently using for the dog. In the trot gait, one front leg and its’ contralateral rear leg are in support, followed by the other front leg and it’s contralateral rear leg. This gait is usually used by the dog at speeds to fast to walk but not fast enough for a run. Some breeds use a pace gait instead of the trot. The pace is similar to the trot except that the right side legs are in support followed by the left side legs. Our system is capable of analyzing a dog in a pace gait.

The trot gait is a symmetrical, two-beat gait

The Phases of the Trot Gait

Locomotor Actions during the Trot gait in the dog.

Locomotor Actions during the Trot gait in the dog in slow motion

Gaits used by the Dog

Walk

Locomotor Actions during the walking gait.

Cantor

Locomotor Actions during the walking gait.

Transverse Gallop

Locomotor Actions during the transverse gallop gait in the dog in slow motion.

Double Suspension Rotary Gallop

Locomotor Actions during the Double Suspensory Gallop gait in the dog in slow motion.

Lameness

Lameness is defined as a variance from normal gait. There are two types of lameness: anatomical and pathologic. Anatomical lameness may not necessarily be from pain, and can be genetic or acquired. Pathological lameness can be neural or musculoskeletal. Musculoskeletal lameness is usually caused by pain . Two diagnostic tools to assess lameness are gait analysis and the physical exam. The amount of variance from a normal gait is defined in degrees of lameness.

Most abnormalities can be detected with subjective gait analysis. A dog with a lesion causing severe sharp constant pain will carry the limb and keep the weight off it when lying down. A dull aching pain will produce a limp during the gait analysis. A lesion that produces a small pain that occurs in certain phases of locomotion allows the dog to adjust its gait for relief. The quadruped has the ability to minimize pain by altering movement in such a way that the abnormality may be unnoticeable. This altered gait can lead to subsequent orthopedic problems.

Gait Analysis

This article was published in the Auburn University Sports Medicine Program Newsletter, Summer Issue (pp 1-2) 1998.

The Importance of Including Gait Analysis in the Training Regimen.

Robert L. Gillette, DVM, MSE

Sports Medicine Veterinary Services

Motion is the one common component of all athletic competition. Motion is a result of nerves stimulating muscle to move bone. Abnormal motion occurs when this chain of events is disrupted. Locomotion of an animal is described as its gait. The walk, trot, and gallop are three forms of gait. Gait analysis is used to assess the movement of each of the individual joints and how this movement affects locomotion.The canine athlete can present uncommon challenges to the general practitioner. If the pet owner is only interested in companionship, minimal stress will be put upon the body. As the athletic demands of the owner increase there is a proportional increase in the physical demands placed upon the animal’s body. These increased demands placed upon the animal introduce a higher risk of injury.There are four conditions that can impede performance: 1) pain, 2) fatigue, 3) depressed psychology (drive), and 4) impaired health status. In general most canine athletes are healthy, but their health status should be checked at least once a year. In healthy dogs their drive to perform is both inherited and/or acquired through a good training program. A good training program will maintain the conditioning level of the dog at a level that should eliminate the effects of fatigue. Pain is the most common cause of performance impairment and should be analyzed first. Minor pain that does not induce a lameness can show symptoms similar to the problems seen with fatigue or drive. Major pain will inhibit performance.

The canine structure is divided into segments when analyzing motion. The axial vertebral column is made up of many joints and is divided into anatomical segments. The cranial segment is the head, followed caudally by the neck (cervical), thoracic, abdominal (lumbo-sacral), and tail. The appendicular segments are the front legs and the back legs. These are subdivided into smaller segments by the leg joints: shoulder, elbow, carpus, hip, stifle, tarsus & phalanges. Locomotion as a whole is a result of the individual movements of these segments.

Dogs and horses have the ability to minimize pain by altering movement in such a way that the abnormality may be unnoticeable. This ability allows subclinical pain to go unnoticed by the trainers, and handlers. Computer-assisted videographic (CAV) gait analysis can be used to assess to what extent minor pain has an effect on the musculoskeletal system as a whole. In a normal trot the movements of the body are symmetrical. This means that the movements of one side of the body mirror the movements of the other side (Figure 1a). A minor “sprain” of the right carpus not only creates an alteration in the movement of the right carpus but also the left hip and left tarsus (Figure 1b). The back, or axial skeleton, is also affected, since it is the frame through which this alteration is transferred. This can initiate two problems in the athletic or working animal, one biomechanical and the other psychological. First, due to the high activity level of the athletic animal, this alteration caused by the primary injury can lead to secondary and tertiary pain or injuries in the back or other limbs. Secondly, it can create a loss in psychological drive. The dog might begin to associate pain with its workouts.

Trainers and handlers should include lameness examinations in their training and conditioning programs. A lameness examination includes visual gait analysis and physical palpation. Visual gait evaluation can be done once a week or once every two weeks, this allows for early lameness detection. If a gait alteration is detected, the dog should be referred to a veterinarian for a physical examination and definitive diagnosis. Rehabilitation time is relative to the level of injury and the chronicity of the injury. The longer a lameness goes undetected the longer it takes to recover from the body’s adaptations.

Subjective gait analysis is the most common diagnostic tool to assess lameness. It starts by observing the animal while it is at rest, looking for conformational abnormalities or abnormal stances. For example, does the dog seem to hold one leg up or put most of its body weight on a particular leg. After these observations are noted the animal is analyzed while moving. The trot is the best gait to use for analysis, it gives the best picture of abnormal gait. If one of the segments is impaired the gait will be out of balance. The patient is observed moving in a straight line toward and then moving away from the evaluator. Next the dog should be assessed moving in a straight line from the right side and then the left side. Then it should be observed moving in a circle, once clockwise then counter-clockwise.

Most gait abnormalities can be detected with subjective gait analysis. A dog with a lesion causing severe sharp constant pain will carry the limb and keep the weight off it when lying down. A dull aching pain will produce a limp during the gait analysis. A lesion that produces a small pain that occurs in certain phases of locomotion allows the dog to adjust their gait for relief. This altered gait can lead to subsequent orthopedic problems.

Pain is an important performance inhibitor. When compared to the active dog, subclinical pain of the companion pet does not greatly affect the musculoskeletal system. Usually anti-inflammatory therapy is sufficient. In the physically active or competitive animal any pain or lameness should be addressed as soon as possible before these problems affect performance. Gait analysis and physical examination are two useful diagnostic tools for the trainers and veterinarians working with the animal athlete.